You may have heard that Jill Abramson the former executive editor of the New York Times, was recently fired. I’ve been living the life of an academic hermit for the past couple of weeks, so thankfully Lynne Murphy (Reader in Dept. of Linguistics, University of Sussex) alerted me to the issue and pointed out that Abramson’s leadership and professional behavior were being described using potentially gendered language. Murphy noted in particular the use of pushy, and reading about Abramson in various articles (for example, here, here, and here), I found her described in numerous ways pushy, brusque, stubborn, and condescending.

Given what I have previously documented for bossy, I was certainly suspicious of the possibility that these descriptions had an element of gender bias to them as Murphy and various writers covering the topic have been as well. Ken Auletta raises the issue of gendered perceptions of Abramson’s behavior in The New Yorker:

Several weeks ago, I’m told, Abramson discovered that her pay and her pension benefits as both executive editor and, before that, as managing editor were considerably less than the pay and pension benefits of Bill Keller, the male editor whom she replaced in both jobs. “She confronted the top brass,” one close associate said, and this may have fed into the management’s narrative that she was “pushy,” a characterization that, for many, has an inescapably gendered aspect.

In a search for evidence of this “gendered aspect”, I used a very similar technique to my past research on bossy (see also my recent post on articulate). I gathered a random sample of 200-300 occurrences of all of the adjectives listed above from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA). I read through them and determined whether each term was used to describe a person or some aspect of a person (their tone, their personality, and so on). I discarded instances of the term not used to describe a single person (such as “It left a stubborn stain”, or “Her parents were extremely pushy“). My final samples contain about 120 uses of each term.

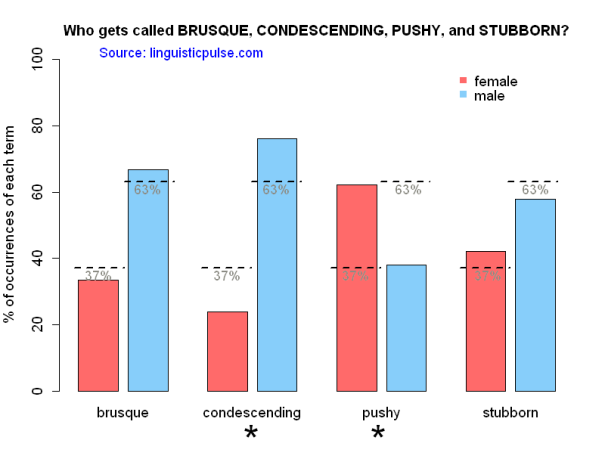

In a previous post, I estimated that women account for about 37% of the individuals mentioned in COCA, while men account for the remaining 63%. Thus, in order to see whether women are described using these adjectives more frequently I tested to see whether the use of any of these terms for women occurred at a rate significantly higher or lower than the 37% baseline. What I found is presented in the graph below.

I did not find that brusque or stubborn were used in a gendered manner, at least not to a significant degree (of course, whether there are fine-grained differences in how the terms applied to men and women is not observable through my method and remains a possibility). In other words, these two words were used for men and women at about the rate we might expect given that women represent about 37% of the people mentioned in COCA.

I did, however, find significant gendered usage for the other two terms: pushy and condescending. The gendered use of pushy shows remarkable similarity to that of bossy. Women are labelled pushy about twice as frequently as men in COCA even though men are mentioned nearly twice as frequently as women. As I have argued in past discussions of bossy, this extreme gendered usage likely reflects perceptions that are biased by gender roles. In other words, women are not necessarily more likely to exercise authority but are more likely to be socially sanctioned for doing so due to the perception that they are acting in a manner that is socially unacceptable for women. Men it would seem have a great deal more latitude to exert authority without drawing such criticism.

Interestingly, I found that men are somewhat more likely to be labelled condescending than women, although this tendency is weaker than the gender biases observed with pushy and bossy. About 76% of all instances of condescending were used for men, while men account for an estimated 63% of the individuals mentioned in the corpus. It is tempting to declare that a balance has been struck, that men’s authority is also subject to social policing just using different labels. I would agree that this demonstrates clearly that men are not free to exert authority as they wish, and that words like condescending do work as a form of social sanction on what are perceived as abuses of authority. However, condescending seems to differ from pushy and bossy in an important way, namely that it seems to acknowledge the target’s authority and power even if it does not fully accept it. Consider this example about Bill Gates where Gates’ “condescending” behavior stems from his apparent brilliance and power.

He [Bill Gates] is, like many brilliant people, a bundle of contradictions. He can be acerbic, condescending, and even rude — around Microsoft, he’s notorious for chastising subordinates who, in his eyes, haven’t done their homework — yet he can also be a sentimental, almost sappy guy; he likes Frank Sinatra’s music, Cary Grant’s movies, and The Bridges of Madison County.

Of course, condescending is not exclusively used in cases where the speaker personally fully accepts the target’s authority or power. Sometimes the speaker is specifically using the term to critique the power and authority that has been, in the speaker’s view, wrongfully bestowed on the target or is being over-exercised as in the example below from news coverage of the Casey Anthony trial.

I think that their [the Casey Anthony defense team’s] primary concern should be resentment of the high flying business developer who kind of acts like he’s the boss in any situation, even when he’s talking to the cops. Well, I hate to say it, but we should get a lawyer in here. He’s very flip and he’s a little condescending. And I think in his head he may have a misconception that kind of like Warren Jeffs that whatever he says goes, no matter what.

We can compare this to the way that pushy is used. It is particularly enlightening to consider who besides women are labelled pushy. One such group, often labelled pushy, are salespeople.

One hint of a swindle, he says, is when a pushy salesman tries to get you to sign on the dotted line before you’ve had a full chance to investigate.

Here it appears that the salesman simply exerts power without any explanation given as to where the sense of power and authority might be stemming. Indeed, I imagine that most people view the relationship between a salesperson and a customer as one in which the customer should be the one with the legitimate claim to power. Thus, the use of pushy highlights the illegitimacy of the salesman’s attempts to exert power.

Another example comes from a reader’s letter to the San Francisco Chronicle commenting on a story about a mother and her child’s complaints about the public library.

An overachieving 11-year-old and his pushy mother can’t have things their way at the San Francisco Public Library and whine about it to a supervisor…

The pair are described in terms that seem to highlight the fact that they have no claim to authority or power. The child’s age is highlighted, and the two are described as ‘whining’. Compare these examples of pushy to those of condescending above. Gates’ perceived condescension is explained (if not excused) by his status as the boss and his brilliance. The business developers’ alleged condescension is explained (if not excused) by his authority in other matters, such as being ‘the boss’ elsewhere in his professional life. It seems then that while condescending is not a positive description, it seems to describe an abuse of power as opposed to an illegitimate claim to power as bossy and pushy are more likely to do.

Returning briefly to the media coverage of Abramson, it’s not really my intention to adjudicate whether Abramson is the victim of sexism. There are of course many other aspects of the story that I’m not privy to. However, this analysis can elucidate one particular issue. Abramson is being described with at least one term that seems to be used especially frequently for women: pushy. I think it’s important to note here who is describing Abramson as pushy. Those higher than her on the New York Times’ hierarchy, who had the power to fire her, characterized her as pushy, according to Auletta’s New Yorker article. In contrast, those beneath her in the same hierarchy described her as condescending. This division fits with the use of the two terms I noted above. Her employees may see her claim to authority over them as legitimate but perceive her as abusing it, whereas her superiors view her as having no legitimate claim to exert authority over them. This is not to say that gender plays no role in this particular case, but it does highlight the limitations of the type of analysis I’m doing for addressing that question.

I was listening to NPR’s “Tell Me More” this morning about Jill Abramson, and thought that this would be interesting for you to investigate in the same way you did with the “Bossy” posts. Glad to see you did! Natalie Nougayrede also resigned, the same day I think, from her post as editor of the French newspaper “Le Monde,” and on the show, Susan Glasser, editor at Politco, discusses how similar the same epithets were used for both women. In her essay, Editing while Female (5-16-14) she writes,

“But what I’m struck by is the depressing circularity of the whole conversation. You don’t have to pronounce judgment on the merits of Abramson’s tenure to be dismayed by the awful sameness of the charges that are hurled by those anonymous newsroom sources. The women are always labeled smart but difficult, unapproachable and intimidating. It is always, of course, mind you, not a question of their journalistic merits but of their suitability, their personality. And eventually of course their publishers or boards give in to the narrative too. Maybe there were serious policy disagreements, fights about how to handle change or even plain old-fashioned power struggles. But that is never what’s cited as the official rationale when the ax falls on these women. And why should it be? There is already a narrative out there, a convenient excuse. It’s about “management style” or “communication.”

It made me curious as to how broadly similar gender biased terms are used across different languages such as English and French, and I wonder if there is corpus linguistic research that has looked at something like this from a comparative perspective? If not, that might be something interesting to explore!

Tell Me More 5-19-14

[…] State University linguistics PhD student Nic Subtirelu, who runs the Linguistic Pulse site, gathered a random sample of 200 to 300 occurrences of each of the above adjectives […]

[…] have centered on the word “condescending.” This is due in a large part to some work done by Nic Subtirelu, a linguist at Georgia State […]

[…] a Ph.D. student in the Department of Applied Linguistics and ESL at Georgia State University, wrote on his blog Linguistic Pulse that he was “suspicious of the possibility that these descriptions had an element of gender […]

[…] a Ph.D. student in the Department of Applied Linguistics and ESL at Georgia State University, wrote on his blog Linguistic Pulse that he was “suspicious of the possibility that these descriptions had an element of gender […]

[…] a Ph.D. student in the Department of Applied Linguistics and ESL at Georgia State University, wrote on his blog Linguistic Pulse that he was "suspicious of the possibility that these descriptions had an element of gender bias to […]

[…] a Ph.D. student in the Department of Applied Linguistics and ESL at Georgia State University, wrote on his blog Linguistic Pulse that …read […]

[…] a Ph.D. student in the Department of Applied Linguistics and ESL at Georgia State University, wrote on his blog Linguistic Pulse that he was “suspicious of the possibility that these descriptions had an element of gender […]

[…] a Ph.D. student in the Department of Applied Linguistics and ESL at Georgia State University, wrote on his blog Linguistic Pulse that he was “suspicious of the possibility that these descriptions had an element of gender […]

[…] a Ph.D. student in the Department of Applied Linguistics and ESL at Georgia State University, wrote on his blog Linguistic Pulse that he was “suspicious of the possibility that these descriptions had an element of gender […]

[…] cites a study done by Georgia State University linguistics PhD student Nic Subtirelu, who runs the Linguistic Pulse site. He gathered a random sample of 200 to 300 occurrences of each of the adjectives (pushy, stubborn, […]

[…] dall’insistenza di questi aggettivi, Nic Subtirelu, un dottorando del Dipartimento di Linguistica applicata dell’Università Statal…, ha studiato i pregiudizi di genere insiti nel modo in cui, negli Stati Uniti, si parla della […]

[…] “irragionevole”, “assillante”. Incuriosito dall’insistenza di questi aggettivi, Nic Subtirelu, un dottorando del Dipartimento di Linguistica applicata dell’Università Statale de…, ha studiato i pregiudizi di genere insiti nel modo in cui, negli Stati Uniti, si parla della […]

Reblogged this on The Life Of Von and commented:

Amazing to think a woman can be described as ‘pushy’ for querying why her entitlements were less than that of the man preceding her in the job.

[…] women were labelled ’pushy’ twice as frequently as men despite the fact men are mentioned nearly twice as frequently as women overall in the COCA. […]

[…] and magazines between 1990 and 2012, linguist Nic Subtirelu found women are called “pushy” twice as frequently as men and “bossy” nearly three times as […]

[…] of performance reviews, women are called bossy nearly three times as frequently as men and pushy twice as […]

[…] of opening reviews, women are called dominant nearly 3 times as frequently as group and crude twice as […]

[…] provoking analysis from the blog “Linguistic Pulse”shows the gendered nature of the use of the word […]

[…] and academic text, women were twice as likely to be labeled as pushy than men. Nic Subtirelu wrote about this issue and mentioned that while men were more likely to be described as condescending, there wasn’t […]

[…] cites a study done by Georgia State University linguistics PhD student Nic Subtirelu, who runs the Linguistic Pulse site. He gathered a random sample of 200 to 300 occurrences of each of the adjectives (pushy, stubborn, […]